A Brief Genealogy of Occupy Wall Street

Despite recent characterizations of Occupy Wall Street as merely a Left response to the present economic depression, the movement has a rather long, if discontinuous, history. The frustration displayed by establishment analysts and journalists towards the movement’s so-called “lack of specific demands” and inability — at least in the present moment — to be integrated into formal party politics is emblematic of a particular character the European and North American Left has assumed, really, since the failure of the Third Road of Eurocommunism in Italy and France in the early 1970s, the failure of our tragic heroes of 1968 to carry out a sustainable structural revolution, and the development in the West of an underground, radically democratic cultural politics that has operated more or less outside of organized political and economic structures since the 1970s.

Notwithstanding the proliferation of contemporary fantasies that dutifully characterize the period between the 1940s and early-1970s as some sort of “Golden Age” for labor, accountable governance and liberal democracy, European and North American Leftists during the height of Keynesianism were baffled by the ease with which social democratic parties were co-opted into alienating capitalist structures that promised consumer prosperity at the expense of a socialist society. Everyday life in the postwar era was increasingly becoming highly commodified, and capital more monopolized. Political life was highly bureaucratized, Jack Kerouac hit the road and discovered the East, while Ginsberg read in a park, and the limited democratic nature of Western states led to many clashes between movements and police powers. American imperial might was in full display in Latin America and Southeast Asia, and the postcolonial hopes of people in the global south were stymied over and over again by a consistent instigation of dirty wars by the United States and Soviet Union. And on the horizon, a man-made ecological calamity of the first order was just beginning to be understood.

In order to account for the large transformations occurring in everyday life, the Left began to rethink the tacit presuppositions within Marxist theory — like the proletariat as the privileged subject of history and the extent to which the economic “base” determined the superstructure — and in many cases, abandoned Marxism all together. Culture and politics became the privileged points of critical analysis, and a radical rethinking of race, gender, sexuality, participatory democracy, colonial power structures, indeed the very nature of power took place. At the same time that a participatory, radically democratic political culture began to take root in Europe and North America (what the mainstream called “countercultures”), power was increasingly perceived not as something held by a centralized state, but rather something that circulated within and through bodies, material spaces, language, immaterial labor, and (psychoanalytical) cultural/ideological structures. The effects of this epochal shift were not confined to analyses of politics, economics and society. Within the sciences and military apparatus too, this was the moment when theories of complexity and chaos, networked power relations and wo/man-machine hybrid structures began to gain currency as scientists, mathematicians and computer programmers worked to determine how order emerged almost spontaneously out of irregularity and chaos in the “real world,” marking a real departure from Euclidean and Newtonian deterministic foundations.

In retrospect, this time commonly is referred to as the nascent period of “identity politics,” and many new spaces emerged to facilitate and (re)produce these new movements: food and living cooperatives; new (anti-Reagan) underground music scenes (hip hop, punk, no wave, indie, hardcore, metal, goth, noise, techno, etc.) that grew within new spaces and the democratization of technology; identity-based neighborhoods (e.g., GLBT sections of town); vegetarianism; small-plot farming (a desire to recover another lost agent of history: the authentic peasant);environmental initiatives and spaces; anarchist bookstores; coffee shops and cafe culture; and entirely new architectural spaces based on interactive pods and segments rather than mass factory-like enclosures. A massive proliferation of computers and machines facilitated new forms of heterogenous communication and cultivated an entirely new way of thinking among the Left, oriented more towards information, a DIY ethic, consensus-based models of decision-making, and an increased privileging of political participation and listening over strictly economic struggles (though these were still powerful, in spite of dwindling union power).

During the time that this dispersed, non-mainstream, heterogenous new Left was beginning to take shape, and having account for itself against the animus and/or agnosticism of more mainstream liberals and Marxists who discounted the emergence and consequences these new “identity movements”, several crises of capitalism were resulting in a profound reorientation of capital away from mass organized manufacturing, towards a more “flexible regime of accumulation.” That is, a form of neoliberal capitalism which relied heavily on cheap (non-unionized) labor, mass computing and automation, niche domestic markets, a global division of labor and market, a scaled-back government that regulated “at a distance”, and an abundance of finance capital to speculate on market trends and futures. Sparked by the 1973 oil-crisis, the emergence of this new regime of capital accumulation took on a brazenly predatory form, pillaging and privatizing vast swaths of the global south, ransacking economies through structural adjustment programs that hollowed out states while enriching elites at the expense of stable economies that could benefit the many. Many of the areas subjected to structural adjustment programs, especially in the African subcontinent, were so devastated that they easily succumbed to a near state of permanent war between warlords and cartels, with little state control outside of repressive military powers, while a privatization bonanza has been occurring within the continent for rare minerals and oil.

These two movements — a radically democratic Left not beholden to orthodox Marxist theory, and neoliberal social organization and economic organization — came to head in the famous 1999 clash at the WTO meeting in Seattle. The Leftist movement, a broad coalition of diverse groups largely self-identifying as anti-capitalist and/or anti-globalization, had relatively simple demands that sound very familiar today: to end a form of predatory capitalism that has taken a violent toll on large parts of the United States (the “rust belt”) by moving manufacturing and economic activity overseas or south of the border; to end a form of capitalism that has been a mask for a new imperialism, subjecting populations across the global south to exploitative wage slavery for the benefit of a small group in the global north; to end a form of capitalism that has been an ecological disaster, and has the world heading towards a real global catastrophe if its basic form goes unchanged; to end a form of capitalism that has been fundamentally antidemocratic, depriving everyday people of any real say in how their economic activity should be organized; and, finally, to end a form of capitalism that has been cultural violence of the first order, placing unchecked individual desires and market relations ahead of communities, intellectual labor, and forms of self-fulfillment that can blossom outside of a social structure that reduces inner- and external-life to a commodity relation.

While the 1999 action in Seattle was ultimately a success, and built momentum that quickly spread around the world, leading to unique forms of transnational organizing (e.g., the World Social Forum), the movement quickly faded after 11 September, 2001. In the aftermath of 11 September, much of the anti-globalization movement’s energy understandably moved towards organizing against the imperialist wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, resulting in a series of defeats from a radically antidemocratic and unresponsive Bush Administration in the US (and Blair in the UK) that was hellbent on war, and enriching the economic elite through devastating tax cuts and a privatization binge on critical state institutions, from education to war itself. The Bush Administration also carried out a systematic attack on a particularly active segment of the US ecological movement, conflating tree-sitters who sought to prevent logging with terrorists, effectively destroying such groups as Earth First! and the ALF. The Bush Administration, with Democratic Party enthusiasm (Russ Feingold being the lone dissenting voice), also erected a massive surveillance architecture, the consequences of which are still being felt and worked out today.

These setbacks deflated the radically democratic Left for a number of years, largely through “activist fatigue” (myself included). However, during the Bush and Obama administrations, whole new forms of organizing were taking place, with a new generation of young people growing up within the technocultural apparatuses of “social networks” and “virtual politics.” For many years, the effectiveness of these new technologies for political-economic change was both limited and subject to criticism. Although I rarely ever quote Thomas Friedman, he once wrote that “virtual politics is just that: virtual,” and many people on the Left (myself included) adopted that stance. Small skirmishes with the state apparatus and economic structure continued through the 2000s, largely around issues of police brutality, the expansion of the prison-industrial complex, the right-wing attack on vulnerable populations (e.g., immigrants and intellectuals), and economic justice, especially in the wake of Katrina’s destruction of New Orleans in 2005. But, these small skirmishes had little common ground or space to work together.

In the meantime, after 2008, the political disorganization of the Left had two profound consequences: (1) untapped youth energy was organized and appropriated within conventional Democratic Party politics (the election of Obama), and (2) the lack of a critique of capitalism and post-capitalist program left wide swaths of the American population who were victims the 2007-2008 Financial Crisis open to a right-wing nativist assault. The rise of the so-called “Tea Party” played on xenophobic, economic fears, and a highly particular American “origins story” of the intent of the Founding Fathers to create an enemy out of an already hollowed-out state, and advance an anti-tax agenda that only enriches the very few (the “1%”) and the expanse of the many (the “99%”). Ideologically, this right-wing movement appealed to an all-too-American worldview that each individual is the maker of his own destiny (the entrepreneurial fantasy), which has had profound effects (for the worst) on popular, everyday discourse within the United States, and increasingly in Europe.

But, since the beginning of this right-wing, quasi-fascist nativist advance, there has been a reaction, both mainstream and among the Left, resulting in a slow but measured development of a Leftist rebirth over the past two years, especially among disenchanted Obama supporters. The “Save the University” movement against university cuts across the U.S., but especially in California, and the explosion of popular discontent in Madison, Wisconsin around stripping collective bargaining rights for public employees have been signature moments of this rebirth.

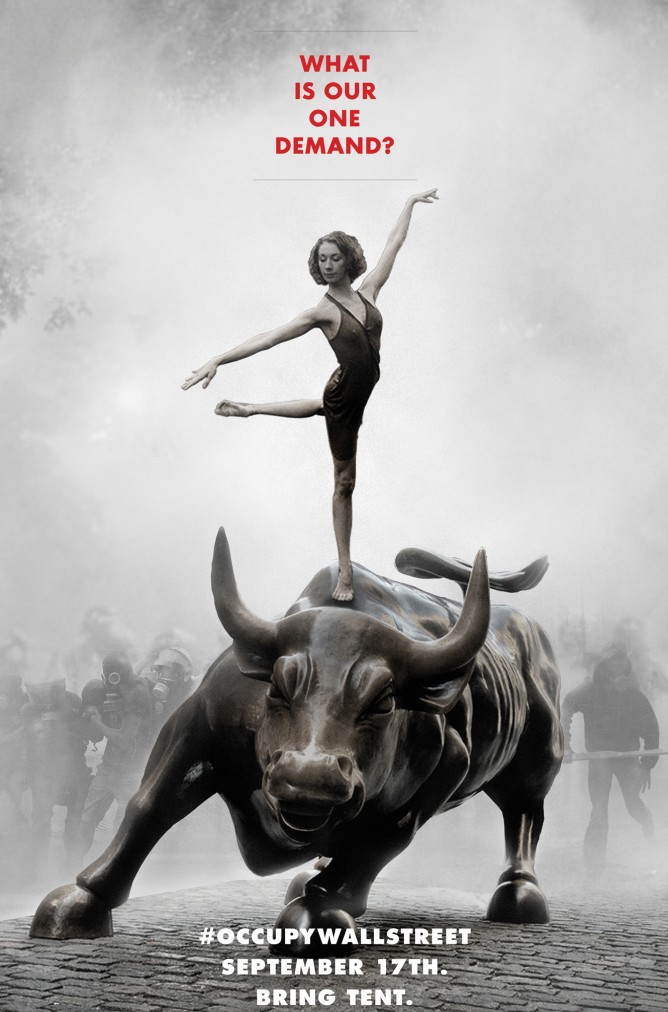

The real catalyst, however, for Occupy Wall Street did not happen within US borders, but rather in what has been dubbed “The Arab Spring,” which sparked in Tunisia, and quickly spread like a benign tempest through Egypt, Bahrain, Palestine, Syria, Yemen, to a certain extent Libya, and beyond (explaining my measured inclusion of Libya is beyond the scope of this commentary). What the world witnessed in Egypt was the power of occupying space (Tahrir Square) coupled with numbers, and new technologies and media outlets that can spread information quickly in real time. Also, the indignados movement in Spain against high unemployment and capitalism, and the remarkable Greek protests over the past couple of years served as examples for OWS. In July, Adbusters put out a call to Occupy Wall Street on September 17, and with the work of New York City’s General Assembly, the occupation has proved to be a resounding success and, at the time of this writing, has spread to over 900 cities in 80 countries. This past weekend (October 15th) was a huge day of international solidarity, with well over a million people worldwide protesting against finance capitalism writ large. Even the New York Times, characteristically going with a lowball figure, estimates 100,000 people protested across U.S. cities, mostly on the west coast, far from Wall Street.

What we are seeing now is a rebirth of the radically democratic Left, the essence of which, by its very principles, cannot be co-opted into mainstream political party structures. Without a doubt, this is the most sustained everyday people’s movement with massive numbers within the United States in our lifetimes, and the first “unemployed movement” since the 1980s. We have already witnessed the largest police arrest in US history, with over 700 people arrested on the Brooklyn Bridge on October 1st. Significantly, we are seeing the first sustained imbrication of real-time technologies (including the deft use of social networking, blogging, and livestreaming) and the improvisation of new technologies (the call-and-response “human microphone”) within these movements. The work of Anonymous and Wikileaks attests to the innovative ways in which the radical Left can work in and through these new technologies, while reclaiming the public by occupying material space. These are the kinds of developments that lay the grounds for sustainable momentum. We’ll see where this heads.

I have included a reading list of what I think are significant books for thinking about the genealogy of Occupy Wall Street. There are a couple of other reading lists out there (here and here), but they mostly provide analysis of the financial crisis or are oriented towards pragmatic organization techniques. While they are important, I wanted to provide a list that opens up a way for understanding the theoretical genealogy through which the Occupy movement is operating. The list, like the genealogy above, is not meant to be comprehensive, and I’m open to hearing more suggestions.

Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism, by Lucien van der Walt and Michael Schmidt

Capital, Volume 1, by Karl Marx

One Dimensional Man, by Herbert Marcuse

The Autobiography of Angela Davis

The Wretched of the Earth, by Franz Fanon

Beloved, by Toni Morrison

Our Word is Our Weapon, by Subcomandante Marcos

Orientalism, by Edward Said

Animal Liberation, by Peter Singer

The MonkeyWrench Gang, by Edward Abbey

Gender Trouble, by Judith Butler

Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, by Ernesto Laclau and Chanel Mouffe

Contigency, Hegemony and Universality by Butler, Laclau and Zizek

A Thousand Plateaus, by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari

Empire/Multitude/Commonwealth, by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri

The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It), by J.K. Gibson Graham

No Logo, by Naomi Klein

The Coming Community, by Giorgio Agamben

Days of War/Nights of Love, by Crimethinc.

A Hacker Manifesto, by McKenzie Wark

Neuromancer, by William Gibson

The Coming Insurrection

Dieses Werk ist unter einer

Dieses Werk ist unter einer Creative Commons-Lizenz lizenziert.

Trackback URL:

https://rageo.twoday.net/stories/49585284/modTrackback